Howker Ridge Trail Info

Detailed information about the Howker Ridge Trail — length, elevation gain, terrain, water sources, and historical context for trip planning.

⚠️ Important Trail Warnings

Trail is not frequently traversed in winter and should be expected to break a majority or the entirety of the trail at any given time from October until May.

With weather in careful consideration, take note of exposure signage and trailhead notices and recommendations from the USFS before entering exposed or alpine areas & zones.

Notice: This page is for background information only and is not intended for emergency planning. Unofficial information compiled by the trail adopter and trusted references.

Table of Contents

- 📊 Trail statistics

- ✨ Highlights

- 🏞️ Trail Geography & Topography

- 🚗 Trail Access & Parking

- 🧭 Trail Difficulty, Distance & Time

- ☀️ Seasonal Conditions & Best Times

- 🌿 Ecology & Wildlife

- ⚠️ Trail Safety & Hazards

- 📷 Viewpoints & Photography Spots

- 🖼️ Photo Gallery

- 🗺️ Trail History

- 🔨 Trail Construction

- 🧹 Trail Maintenance & Stewardship

- 🔗 Trail Connections & Networks

- 🔁 Howker Ridge Loop (Randolph East) Options

- 🛌 Nearby Lodging & Facilities

- 📍 Points of Interest

- 📷 Second Photo Gallery

- ❓ Frequently Asked Questions

| Length | ≈ 4.5 mi = 4.2 mi + .3 mi (Osgood Ridge) one-way. |

|---|---|

| Elevation gain | ≈ 4,750 ft = 4,450 ft (ascent) + 300 ft (descent). |

| Typical time (round-trip) | ≈ 6–10 hours. |

| Difficulty | Strenuous / hard. |

| Terrain | Rocky, steep ridgeline with scrambles over the Howks and alpine exposure. |

| Water sources | Lower Bumpus Brook; spring near Pine Link junction; hut (seasonal). |

| Designations | White Mountain National Forest; intersects the AT (Osgood Trail); NH 4,000-footer list. |

| Trailhead & parking | Randolph East (Pinkham B / Dolly Copp Rd); lot typically plowed in winter; alternate Appalachia lot. |

| Camping nearby | AMC Madison Spring Hut (seasonal); Valley Way Tentsite; RMC cabins / Perch. |

| Dogs | Allowed. |

| Bailout Routes |

Watson Path (Diretessima) Airline (Easiest Grade) Valley Way (Exposure Safety) Pine Link (Dolly Copp Rd. Alternative) |

| Historical note | Named for the Howker family; a classic northern Presidential route. |

- Four alpine Howks: A classic scramble over four rocky knobs with expanding views toward the Northern Presidentials.

- Waterfalls and gorges: Bumpus Brook’s cascades, including Hitchcock Falls and Devil’s Kitchen, add dramatic scenery in the lower miles.

- Summit connection: The route links directly to Mount Madison and the Appalachian Trail for a high-alpine finish.

- Quiet wilderness feel: Compared with busier routes, Howker Ridge retains a rugged, less-traveled character.

The Howker Ridge Trail ascends the north side of Mount Madison, following a spur ridge that separates two drainages. For the first mile, the trail parallels Bumpus Brook, a tumbling stream that carves a mossy ravine through hardwood and spruce forest. Here the terrain is gentle by White Mountain standards — hikers traverse bog bridges and moderate grades while the brook plunges over cascades in a cleft beside the trail.

Notable features include the Devil’s Kitchen, a steep-walled mini-gorge where the brook churns, and nearby waterfall plunges that have carved potholes into the granite streambed. As the trail leaves the brook and climbs onto the ridge, the topography shifts to steeper slopes and rocky outcrops.

Above ~2,500 feet, Howker Ridge narrows into a spine with increasingly panoramic aspects. The trail clambers up four hump-like knobs (the “Howks”), connected by short cols that drop and re-climb. The ridge’s slope steepens, requiring hands-and-feet scrambling over ledges and boulders in places. The environment transitions from dense spruce-fir to krummholz and then alpine tundra as the trail nears timberline around the Third Howk and Fourth Howk.

Above ~4,000 feet, terrain is predominantly broken talus and bedrock. The Howker Ridge Trail meets the Osgood Trail (Appalachian Trail) on Madison’s summit cone, where the topography eases into the broad dome of Mount Madison (5,366 ft).

The Howker Ridge Trail begins at the Randolph East trailhead, a small dirt parking area just south of US Route 2 on Pinkham B Road in Randolph, NH. Look for a U.S. Forest Service “Hiker” sign and a trail kiosk about 0.1 mile down Pinkham B Road (also called Dolly Copp Road) from Route 2. Trailhead facilities include a pit toilet but no potable water. There is no parking fee.

In winter, the parking lot is typically accessible and plowed thanks to its connection to the rail trail and Randolph emergency services access before the Dolly Copp Road gate closure. During snow season, hikers often begin instead from the large Appalachia parking lot and use connecting trails to reach Howker Ridge.

Driving directions: From Gorham, NH, drive ~4 miles west on Route 2 to Randolph. Turn left onto Dolly Copp Road (marked for the Presidential Range Rail Trail). The trailhead is 0.1 mile in on the left. In summer, Dolly Copp Road can also be accessed from the south via NH 16 through Pinkham Notch (the road passes Dolly Copp Campground). Roadside parking is not permitted along Pinkham B Road, so use the designated lot.

Length and elevation: From Randolph East to the summit of Mount Madison, the Howker Ridge Trail is about 4.46 miles one way. Because the route repeatedly climbs and descends over the four Howks, hikers gain roughly 4,430 feet of total elevation. Plan for a full day (7–9 hours) to cover the ~9–10 mile out-and-back.

Technical difficulty: The trail involves rugged, varied terrain. Lower sections have muddy stretches, roots, and short wooden bridges. As the climb steepens, hikers encounter rock steps, boulder scrambles, and a few spots requiring hands for balance. The Howks present steep ledges that can feel “scrambly.” Above treeline, cairns mark the route over jumbled talus. There is some exposure to heights, but the biggest challenge is sustained elevation gain and rocky footing.

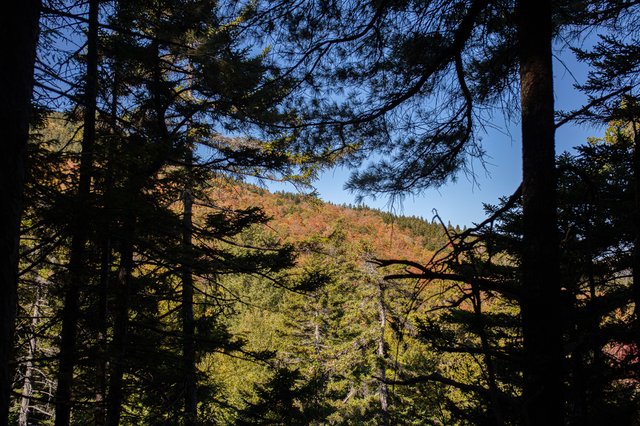

The optimal hiking season is late spring through fall (May through October). In late spring and early summer, Bumpus Brook flows strongly and alpine wildflowers bloom above treeline. Black flies can be ferocious in June, so many prefer mid-summer when bugs subside. Summer offers the most reliable weather and longest daylight, though hikers should be prepared for cold winds or thunderstorms on Mount Madison’s summit even in July.

By late September and early October, fall foliage lights up the surrounding forests.

Winter and early spring ascents are recommended only for experienced mountaineers. The trail is typically not traveled in winter; expect to break trail through deep snow and carry snowshoes plus technical gear. Above treeline, the ridge is fully exposed to Presidential Range weather, with high winds and arctic conditions from November through April. A safer winter strategy is often to ascend Howker Ridge on a clear day and descend via a safer trail like Valley Way.

Hiking the Howker Ridge Trail is a journey through multiple ecological zones. Deciduous woodlands dominate the lower mile: birch, beech, and maple trees arch over the trail until about 2,000 feet. Bumpus Brook’s cold water supports small brook trout and an abundance of mosses and ferns along its banks. The constant cascade of water and deep shade create a cool microclimate cherished by amphibians and delicate plants like foamflower.

Wildlife signs are common — hikers might notice moose tracks near the brook and up the ridge to Pine Link Junction. Black bears are infrequent but possible visitors at lower elevations, and smaller creatures like red squirrels and chipmunks are frequently seen.

Climbing higher, the forest transitions to boreal spruce-fir. Around 3,500–4,000 feet, trees become stunted and give way to krummholz, the gnarled shrub-like spruce/fir at treeline. Above treeline, alpine tundra takes over. Cushion plants and alpine grasses grow in patches among the rocky talus. This area experiences a very short growing season; staying on rocks protects slow-growing plants.

Important: This page is for trip planning only. Weather, snow, and trail conditions change rapidly. Forecasts, GPS coordinates, and third-party feeds may be inaccurate or delayed. By using this page you agree that you are solely responsible for your safety and decisions in the field. Always carry proper gear, check multiple sources, and turn back if conditions deteriorate.

Weather and exposure: The upper ridge and summit are fully exposed to wind, cold, and lightning. Even on a mild day in the valleys, conditions near Mount Madison’s summit can be extreme. Pack warm layers and rain gear year-round.

Terrain hazards: Many sections are steep and filled with loose rocks. Falls and ankle injuries are a risk on rough footing, especially on descent. The Devil’s Kitchen gorge and the Bear Pit chasm are reached by short side paths; anyone venturing off trail should be extremely careful of slippery moss and sheer rock walls.

Seasonal hazards: In winter, steep sections can accumulate hard ice — an ice axe and crampons (plus the skills to use them) are necessary to ascend or descend safely. The route is typically untraveled in winter, so expect to break trail and budget extra time and energy for the climb. After heavy rain or during spring melt, Bumpus Brook crossings can swell and become hazardous. Cell phone service is spotty to nonexistent, so parties must be self-reliant.

The serrated crest of Howker Ridge, dotted with four rocky “Howks,” offers unique vistas on the ascent to Mount Madison. The Fourth Howk is a spectacular natural balcony with sweeping views across the Carter-Moriah Range, the Crescent Range, and distant Maine mountains. Each of the lower Howks also has outlooks: the Second Howk opens westward views of Mount Madison’s summit cone, and the First Howk provides peeks back north toward Randolph Valley.

Lower on the trail, the waterfalls along Bumpus Brook — Stairs Fall, Coosauk Fall, and Hitchcock Fall — are photogenic spots, especially in spring when water flow is highest. Mount Madison’s summit itself is a premier photography spot, offering sweeping shots of the Northern Presidential ridge and the Great Gulf.

📷 Howker Ridge Photo Gallery

A curated set of images from key locations along the trail (converted to WebP for fast loading). Click any image to view full-size.

The Howker Ridge Trail traces its roots to the late 19th century and is named for the Howker family, notably William Howker, who owned farmland at the base of the ridge. Early trail builders Eugene B. Cook and William H. Peek cut this path between 1899 and 1901, establishing a direct route up Mount Madison’s rugged northeast spur. “Howk” became a local term for the ridge’s rocky knobs, and by the early 1900s hikers were already referring to the four peaklets on the ridge as “the Howks.”

By 1916, guidebooks noted open views from spots like Blueberry Ledge on the lower ridge, though today the forest has regrown. The trail remains a less-traveled path to Mount Madison, retaining old-fashioned wilderness charm even as it became part of the White Mountain network.

Logging History in the Randolph East Area

The forests surrounding Howker Ridge Trail have not always been the quiet wilderness we know today. In the 19th century, the lower slopes of Mount Madison and the Randolph valley were humming with human activity—first from subsistence farming and later from extensive logging. Early Randolph settlers cleared and farmed pockets of land at the mountain’s base (in fact, the trail’s namesake William Howker kept a homestead near the present trailhead). But by the late 1800s, the focus had shifted from farms to forests: timber companies cast their eyes on the vast stands of spruce, fir, and hardwood blanketing the Northern Presidentials.

Logging reached into Randolph’s eastern high country in the 1880s and 1890s. Heavily laden horse-drawn sledges and oxen teams became a common sight, dragging logs down from the slopes in winter. Logging crews carved rough tote roads up alongside streams like Bumpus Brook, and they built temporary camps deep in the woods where lumberjacks felled trees throughout the cold months. Pinkham B Road (Dolly Copp Road) itself can trace its origins to this era—improved from an old path into a drivable route to help haul timber and connect Randolph to Pinkham Notch. In some spots, loggers even laid short-lived railroad spur lines to carry timber out, reflecting just how fervent the White Mountain lumber boom had become.

The impact of these operations on the land was dramatic and long-lasting. Hillsides that had been densely forested were left almost completely clear-cut. Piles of discarded branches (slash) and sawdust accumulated everywhere. Without tree cover, spring rains washed out soils on steep slopes, and streams ran silty and wild. Occasionally the smoldering embers of a logger’s campfire or sparks from steam-powered equipment ignited the dry slash, resulting in forest fires that swept across the cut-over mountainsides. By the turn of the 20th century, large tracts of Randolph’s lower elevations were open expanses of stumps, and the once-lush Bumpus Basin was a patchwork of logging clearings. Locals at the time remarked that from Randolph Hill you could look south and see straight up into King Ravine and across the bare flanks of Mount Madison—vistas created not by nature, but by the logger’s axe.

Hiking trails, naturally, suffered during this logging heyday. Many early paths that local adventurers and guides had established (or that the Appalachian Mountain Club had described in its early guidebooks) were disrupted or vanished entirely beneath felled timber. In Randolph, routes had to be reconfigured to skirt around active logging parcels, and trail signs were sometimes removed or destroyed. It’s no coincidence that by 1910, local hikers felt compelled to form the Randolph Mountain Club to reclaim and rebuild the network of paths. The destruction wrought by unchecked logging was a key motivation behind early conservation movements in New Hampshire.

By the early 1910s, the unchecked logging of the White Mountains had begun to slow, and a new chapter of forest recovery was starting. The federal Weeks Act of 1911 enabled the creation of the White Mountain National Forest, which brought much of the cut-over land under protection and management. Logging didn’t cease overnight, but it became more regulated and eventually faded from this particular area as the biggest timber stands had already been harvested. Over subsequent decades, the once-barren slopes gradually greened as young trees took root among the old stumps. Today, hikers ascending Howker Ridge might notice subtle clues of that era—perhaps an old stone property wall, an oddly straight stretch of trail that was once a logging road, or sawn-off old stumps hidden under moss. But overall, nature has healed much of the landscape. The forest you hike through now is largely second-growth, a living testament to the resilience of these mountains after the tumult of the logging era.

Railroad Era at Appalachia and Randolph East

Around the same time logging was booming, another innovation was changing Randolph’s landscape: the railroad. If you’ve ever noticed the level, gravel path that crosses Pinkham B Road near the Howker Ridge trailhead, you’re looking at another piece of local history: the route of an old railroad that once ran through Randolph. In the late 19th century, as logging camps and hotels sprang up in the Northern Presidentials, railroads pushed into the region to serve both industry and tourism. By 1891 a new branch line had been built westward from Gorham, passing right through Randolph at the foot of Mount Madison. This railroad—later operated by the Boston & Maine Railroad—connected to other lines in Jefferson and Whitefield, providing a vital transportation link for the North Country.

During its heyday, the railroad was the lifeblood of local commerce. Freight trains rumbled through carrying tons of timber harvested from Randolph’s slopes, bound for sawmills and the paper mill in Berlin. In winter, boxcars filled with cordwood and giant spruce logs regularly left the region via this line. At the same time, the railroad brought passengers into Randolph, ushering in an era of increased tourism. City folk would ride up on summer trains to escape the heat, bound for grand hotels like the Ravine House or for trailheads to begin mountain explorations. The railroad company established small flag-stop stations along the route to cater to these visitors. The most prominent was Appalachia Station, located at the base of Randolph’s popular path network (near today’s Valley Way trailhead), which became the main stop for hikers and hotel guests. But there was also a tiny depot known as Randolph East Station right by what is now the Howker Ridge trailhead. Imagine stepping off a train there in the early 1900s: you’d hear the locomotive chuff away down the line, and suddenly you’d be alone on a dirt road, at the edge of the forest, ready to start your climb up Mount Madison.

For several decades, these trains were a common soundtrack in Randolph—whistles echoing off the ridges as they delivered mail, supplies, workers, and adventurers. However, as the 20th century advanced, the role of the railroad gradually diminished. The rise of the automobile and the opening of modern highways (like Route 2, just up the hill) meant fewer people and goods moved by rail. The large logging operations wound down, reducing freight demand. By the mid-20th century, regular passenger service on the line had ended, since hikers and tourists now arrived by car or bus. Freight trains still used the tracks occasionally for a time (primarily serving the paper industry in Berlin), but even that declined by the late 1980s. In 1996, the railroad line through Randolph was formally abandoned, ending over a century of rail activity.

Rather than fade into obscurity, the old rail bed soon found a new purpose. In the early 2000s it was converted into today’s Presidential Rail Trail – a multi-use recreational path that runs about 19 miles from the outskirts of Gorham west to the Israel’s River near Cherry Pond. All along this route, history buffs and outdoor enthusiasts can literally follow the footsteps (or rather, the rail ties) of the past. The section by Howker Ridge trailhead is especially scenic: the rail trail there traverses wetlands and beaver ponds with wonderful views up to Madison’s ridgeline. It’s popular for casual walking, biking, and in winter, snowshoeing and snowmobiling. If you park at Randolph East on a summer day, you might encounter cyclists cruising the rail trail or families pushing strollers, all enjoying the gentle grade that once carried locomotives.

As you start up the steep footpath of Howker Ridge Trail, it’s worth reflecting on this juxtaposition of histories. Not far from the quiet woods and cascading brooks, there used to be the hustle and clatter of a railroad serving frontier logging camps and ambitious hikers in long skirts and wool suits. Today the trains are gone, but you can still find reminders if you know where to look—an old stone culvert here, the preserved Snyder Brook railroad bridge near Appalachia, or a section of steel rail repurposed as a boundary marker. The Presidential Rail Trail ensures that this piece of White Mountain history remains accessible. It invites us to travel at a leisurely pace and imagine an earlier time when steam engines stopped in Randolph to unload hikers eager for adventure. In a sense, the rail trail has become another pathway to experience the mountains, linking past and present at the very doorstep of Howker Ridge.

Constructed by local Randolph hikers at the turn of the 20th century, the Howker Ridge Trail was carved out of steep mountainside by hand. Builders Cook and Peek aligned the route along a natural spur ridge, threading past cliffs and waterfalls and over the ridge’s humps. The initial path likely followed game routes and logging traces, evolving into a formal trail with blazes and a primitive footbed.

Given the era of its creation (1899–1901), the trail was built with simple tools: axes and saws to clear blowdowns, and hoes or shovels to cut rudimentary waterbars. The alignment cleverly takes advantage of natural features — following Bumpus Brook for an easier grade early on, then switching to the ridge crest where the footing is solid rock and ledge.

Over time, sections have been improved but the trail still largely reflects original 1900s construction. Stone cairns were added above treeline to mark the route through open boulder fields. Timber steps or bog bridges exist only at a few lower wet spots, leaving most of the climb as a classic White Mountain scramble over roots, rocks, and ledges.

The Howker Ridge Trail is maintained through collaboration between the U.S. Forest Service and the Randolph Mountain Club (RMC). Maintenance is ongoing given the trail’s steepness and exposure. Trail work focuses on preserving the historic treadway, keeping drainage features functioning, and maintaining cairns above treeline that mark the route through open boulder fields.

A recent maintenance push tackled brushing and blowdowns, clearing the corridor and improving drainage features along the lower mile. This proactive maintenance improves hiker safety and protects the mountain environment by keeping users on the official treadway. Hikers can support stewardship by practicing Leave No Trace and respecting trail closures or reroutes.

Randolph Mountain Club (RMC) – A Century of Stewardship

Founded in 1910, the Randolph Mountain Club is a small but influential hiking club devoted to the trails and peaks of northern New Hampshire. For well over a century, the RMC’s purpose has been to build, maintain, and preserve trails in Randolph and the Northern Presidential Range. The club came into being when local summer residents banded together to restore footpaths that had fallen into disrepair (many obliterated by logging at the time). Ever since, the RMC has been a cornerstone of trail stewardship in this region, ensuring that routes like Howker Ridge Trail remain open and well cared for.

Over the decades, RMC volunteers and trail crews have expanded a network of trails that now spans roughly 100 miles across Mount Madison, Mount Adams, and surrounding areas. These paths—many cut or re-cut by the club’s early members—offer hikers quieter alternatives to the more crowded eastern approaches to the Presidential peaks. The RMC’s focus has always been on low-impact, rugged trails that blend into the wilderness. Hikers often credit the club’s dedicated maintenance efforts for the wild, old-time character that trails in Randolph still retain.

In addition to trail work, the Randolph Mountain Club operates several rustic backcountry shelters and cabins on the northern Presidentials. Well-known RMC shelters like Crag Camp, Gray Knob, The Perch, and the log cabin at Limnological Station provide basic overnight accommodations for hikers (usually first-come, first-served, with minimal fees). These sites are purposefully kept simple—no electricity or meals, and you pack in your own supplies—reflecting the RMC’s “leave frills behind” philosophy. Staying at an RMC cabin is a bit like stepping back in time, offering an experience of the mountains much as it might have been decades ago.

Though far smaller than the Appalachian Mountain Club, the RMC has a devoted membership and an outsized legacy in the White Mountains. Each summer the club hosts guided hikes, volunteer trailwork days, and even social traditions (like an annual tea party and square dance) that have been part of Randolph’s community life for generations. This long-standing presence of the RMC in Randolph has helped foster a unique hiking culture on the northern peaks—one that values self-reliance, volunteerism, and deep respect for the mountain environment. Today, the Randolph Mountain Club continues to partner closely with the U.S. Forest Service to steward trails like Howker Ridge, carrying its mission of mountain stewardship proudly into a second century.

Howker Ridge connects to a dense network of Randolph trails. Near the trailhead it shares a starting point with the Randolph Path, a major trunk trail that crosses Mount Adams and Mount Jefferson. Within the first mile, the Sylvan Way connector links Howker Ridge to the Appalachia parking area, enabling loop hikes that pass additional waterfalls.

Farther up, the Kelton Trail splits off near Coosauk Fall and provides access to the Inlook and Brookside Trails. At roughly 3.1 miles, Pine Link Trail merges from the east, and a short descent on Pine Link leads to a spring that can serve as a water source. The trail meets the Osgood Trail (Appalachian Trail) near 5,100 feet on Madison’s summit cone, offering connections to Madison Spring Hut, the Great Gulf, and the broader Presidential Range traverse.

Howker Ridge Loop (Randolph East) Options

Take advantage of the most interconnected trail network in the White Mountains to maximize your enjoyment in New Hampshire's unique Northern Presidential Range maintained by the RMC, AMC, USFS and others.

| Loop | Peaks | Distance/Elevation |

|---|---|---|

Howker Ridge – Watson Path Loop |

Madison | ~9 mi / 4,000 ft gain |

|

Climbs Mt. Madison via Howker Ridge and Osgood Trail, then descends the steep Watson Path. Expect rocky scrambles, waterfalls near the start, and the Inlook overlook on the return via Brookside, Kelton, and Randolph Path. |

||

Howker Ridge – Valley Way Loop |

Madison | ~9–9.5 mi / ~4,300 ft gain |

|

Ascends via Howker Ridge to Mt. Madison and returns on Valley Way, with an optional Brookside detour for cascades and scenic lower footing. A steadier descent than Watson Path while keeping the big ridge climb. |

||

Howker Ridge – Star Lake – Airline Loop |

Madison, Adams | ~10 mi / 5,000+ ft gain |

|

Summits Madison and Adams by climbing Howker Ridge, tagging Madison, then climbing Star Lake Trail to Adams. Descends the exposed Airline Trail along Durand Ridge for sweeping alpine views. |

||

King Ravine – Howker Ridge Loop |

Adams, Madison | ~9–10 mi / 5,000+ ft gain |

|

Approaches Mt. Adams via King Ravine and the headwall scrambles, then traverses Gulfside to Mt. Madison and descends Howker Ridge. One of the most rugged circuits with boulder hopping and ravine scenery. |

||

Howker Ridge Grand Loop |

Madison, Adams, Jefferson | ~18 mi / ~6,600 ft gain |

|

A mega-loop over Madison, Adams, and Jefferson. Climbs Howker Ridge, continues across the Gulfside to Jefferson, then returns via Castle Trail and The Link for a long, rocky alpine tour. |

||

Howker Ridge – Lowe’s Path Loop |

Madison, Adams | ~13–14 mi / ~5,400 ft gain |

|

Climbs Madison and Adams via Howker Ridge and Star Lake, then descends Lowe’s Path to Gray Knob/Crag Camp and returns on the Spur or Randolph Path. Excellent for a long day or overnight at RMC cabins. |

||

Howker Ridge – Kelton & Inlook Ledge Loop |

Inlook Ledge | ~4.0 mi / ~1,400 ft gain |

|

A shorter loop focused on waterfalls and ledge views. Uses Valley Way and Brookside along Snyder Brook, climbs Inlook Trail to the overlook, then descends Kelton and Sylvan Way back to Appalachia. |

||

Howker Ridge – Pine Link – Rail Trail Loop |

Madison | ~10 mi / 4,000–4,500 ft gain |

|

Summits Madison via Howker Ridge, then descends Pine Link toward Dolly Copp and returns on the Presidential Rail Trail for a fast, level finish. A good option to avoid the steeper north-side descents. |

||

Despite its wild setting, the Howker Ridge Trail has access to nearby lodging options — from backcountry huts to front-country campgrounds. The most famous is Madison Spring Hut, an AMC hut located in the col between Mount Madison and Mount Adams. It offers bunks, potable water, and meals in summer season. RMC cabins such as Crag Camp, Gray Knob, and The Perch are reachable via connecting trails for rustic overnight stays.

Dolly Copp Campground lies a few miles south of the trailhead and offers reservation-only sites, restrooms, and access to other trails. Moose Brook State Park in Gorham is another camping option. The town of Gorham has motels, inns, and B&Bs along with gear shops and restaurants. Pinkham Notch Visitor Center and Joe Dodge Lodge are about 25 minutes away and provide additional lodging and services.

Trailhead facilities include a pit toilet but no potable water. Potable water is available at Appalachia parking area (seasonal hand-pump) and at Pinkham Notch Visitor Center.

Points of Interest

The Howker Ridge Trail is sprinkled with natural features and key junctions. The points below are grouped by type — waterfalls & gorge, ridgeline features, and trail junctions — with approximate GPS coordinates, elevation, and significance.

Waterfalls & Gorge

- Stairs Fall (approx. 1,570 ft): A small 10-foot cascade visible about 0.6 miles in, across the brook from the trail. Often dry in late summer but audible after rains.

- Coosauk Falls (44.362833, -71.270633) – 1,614 ft: A 15-foot series of cascades where Bumpus Brook descends into the Devil’s Kitchen gorge. Old side paths reach the brink, but caution is required on wet rock.

- Hitchcock Falls (44.359783, -71.271183) – 1,877 ft: The tallest of the three main falls, just before the trail leaves Bumpus Brook. Offers secluded pools and a good refill spot (filter recommended).

- Devil’s Kitchen Gorge (approx. 1,650 ft): A narrow mossy chasm with steep walls and potholes carved by Bumpus Brook. A short side path reaches a viewpoint at the edge.

- Bear Pit (approx. 1,840 ft): A vertical-walled rock chasm about 20 feet deep, accessed by a short spur. Interesting formation with caution advised near the edge.

Ridgeline & Summit Features

- Blueberry Ledge (44.354783, -71.261750) – 2,612 ft: Once offered open views; now mostly forested. Historical milestone on the climb.

- First Howk (44.348216, -71.259470) – 3,376 ft: First rocky knob with glimpses toward Randolph Valley and the ridge ahead.

- Second Howk (44.340153, -71.261429) – 3,888 ft: Breaks above continuous tree cover with broader views toward Mount Madison and Gordon Ridge.

- Third Howk (44.336426, -71.263518) – 4,009 ft: Marks transition to alpine terrain with panoramic views and nearby Pine Link junction.

- Fourth Howk (44.334951, -71.266614) – 4,052 ft: A highlight viewpoint and true alpine perch with sweeping panoramas.

- Mount Madison Summit (44.328683, -71.276917) – 5,366 ft: A rocky summit with 360-degree views across the Presidential Range.

- Osgood Ridge (44.329251, -71.271722) – 4,987 ft near junction: Appalachian Trail ridge connecting Howker Ridge to the summit cone and Great Gulf.

- Gordon Ridge (44.350067, -71.277300) – 2,746 ft crest: Trailless ridge forming the opposite wall of Bumpus Basin, visible from the Howks.

Trail Junctions & Connectors

- Randolph Path (Trailhead Junction) (44.370767, -71.271300) – 1,299 ft: Diverges near the trailhead and provides a cross-mountain route toward Adams and Jefferson.

- Sylvan Way Trail (44.363017, -71.271017) – 1,644 ft: Connector from Appalachia with gentle grades and access to additional waterfall loops.

- Kelton Trail (44.362167, -71.271667) – 1,768 ft: Splits after Coosauk Fall to connect with Brookside and Inlook trails.

- Kelton Crag (44.360067, -71.275633) – 2,142 ft: Short spur off Kelton Trail to a minor rocky overlook.

- Pine Link Trail Junction (~44.335, -71.264, ≈3,950 ft): Shared section with Howker Ridge and a short descent to a spring water source.

- Howker-Osgood Junction (~5,100 ft): Connection to the Appalachian Trail on the summit cone of Mount Madison.

📷 Second Photo Gallery

Masonry-style gallery featuring the key ridgeline and junction scenes from the points of interest section.

Helpful Links

Frequently Asked Questions

Expand each question to reveal detailed answers based on authoritative references.

View the full FAQ

What is the historical origin of the Howker Ridge Trail, and who were the early builders?

The trail dates back to the late 19th century. Randolph locals Eugene B. Cook and William H. Peek cut a direct route up Mount Madison’s northeast spur between 1899 and 1901.

How did the trail get its name, and what is the meaning of “Howks”?

It honors the Howker family, who owned farmland at the base of the ridge. “Howk” became local shorthand for the ridge’s rocky knobs; by the early 1900s hikers called the four hump-like knobs “the Howks.”

When was the Howker Ridge Trail first constructed, and how did early trail builders create it?

The trail was built from 1899–1901. Cook and Peek hand-cut the path along the natural spur ridge, clearing blowdowns with axes and saws and digging rudimentary waterbars with hoes and shovels.

What improvements or changes have been made to the trail since the early 1900s?

The route largely follows its original alignment. Over time, crews added stone cairns above treeline and occasional timber steps or bog bridges in lower wet spots, but most of the trail remains a classic scramble.

What terrain and landscape features characterize the trail’s geography and topography?

The trail climbs a spur ridge on Mount Madison’s north side. It follows Bumpus Brook through a gentle ravine, then ascends the narrow Howker Ridge, clambering over four hump-like knobs. Above about 4,000 feet it crosses broken talus and bedrock before meeting the Osgood Trail on the summit cone.

Where does the trail begin, and how can hikers access the trailhead?

It begins at the Randolph East trailhead on Pinkham B (Dolly Copp) Road, about 0.1 mile from US Route 2. A U.S. Forest Service hiker sign marks the lot. In winter, hikers often park at the larger Appalachia lot and use connecting trails.

Are there parking fees or facilities at the Randolph East (Pinkham B) trailhead?

The trailhead has a pit toilet but no potable water, and there is no fee to park.

How long is the trail from trailhead to Mount Madison, and what is the total elevation gain?

The one-way distance from Randolph East to the summit is about 4.46 miles with roughly 4,430 feet of cumulative elevation gain due to the repeated ascents over the Howks.

How strenuous is the Howker Ridge Trail compared with other White Mountain hikes?

It is considered a strenuous or hard hike. The lower trail has muddy stretches, while higher sections feature rock steps, boulder scrambles, and steep ledges that may require hand assistance. Cairns mark the route across jumbled talus above treeline.

What is the recommended time to complete an out-and-back hike on the trail?

Plan for 7–9 hours to cover the roughly 9–10 mile out-and-back route, allowing time for elevation gain, scrambles, and scenery.

What seasons offer the best conditions for hiking, and what seasonal hazards should hikers expect?

Late spring through fall (May–October) provides the best conditions. Early summer brings high water and wildflowers; mid-summer offers the most reliable weather, though thunderstorms remain possible. Autumn brings vivid foliage. Winter and early-spring ascents are hazardous due to deep snow, ice, and severe weather.

What ecological zones does the trail traverse, and what distinguishes them?

The lower mile passes through deciduous woodland of birch, beech, and maple. Around 2,000 feet the forest shifts to boreal spruce-fir. Between roughly 3,500–4,000 feet, stunted krummholz dominates. Above treeline, the trail crosses alpine tundra with cushion plants and grasses.

What kinds of wildlife might hikers encounter?

Brook trout inhabit Bumpus Brook; moose tracks are occasionally seen near the brook and Pine Link junction. Black bears are uncommon but possible. Red squirrels and chipmunks are frequently spotted along the ridge.

What safety considerations and hazards should hikers prepare for?

The upper ridge is exposed to wind, cold, and lightning. Steep, loose footing increases the risk of falls, especially on descent. Side paths to Devil’s Kitchen or the Bear Pit are slippery. Winter travel requires crampons, an ice axe, and avalanche awareness; after heavy rain, brook crossings can be hazardous. Cell-phone coverage is unreliable.

What are the best viewpoints and photo spots?

Each Howk offers distinct views: the Fourth Howk is a natural balcony with sweeping panoramas toward Maine; the Second and First Howks provide views of Mount Madison’s summit cone and Randolph Valley. Stairs Fall, Coosauk Fall, and Hitchcock Fall are photogenic waterfalls lower on the trail. Madison’s summit itself delivers 360-degree panoramas.

Which waterfalls and gorges can be visited from the trail, and where are they located?

Key features include Stairs Fall (about 1,570 feet), a 10-foot cascade roughly 0.6 mile in; Coosauk Falls (1,614 feet) in the Devil’s Kitchen gorge; Hitchcock Falls (1,877 feet), the tallest cascade; Devil’s Kitchen gorge itself (about 1,650 feet); and the Bear Pit (about 1,840 feet), a deep rock chasm.

Who maintains the Howker Ridge Trail, and how can hikers support stewardship?

Maintenance is shared by the U.S. Forest Service and the Randolph Mountain Club. Work focuses on brushing, blowdown removal, drainage, and cairn upkeep. Hikers can support these efforts by practicing Leave No Trace and respecting trail closures or reroutes.

What other trails connect to the Howker Ridge Trail, and can hikers create loop hikes?

Early connections include the Randolph Path and Sylvan Way from the Appalachia lot. Higher up, the Kelton Trail links to Brookside and Inlook trails; Pine Link joins around 3.1 miles and offers access to a water spring. The trail meets the Osgood (AT) Trail near Madison’s summit, enabling loops or ridge traverses.

Are there backcountry huts or campgrounds near the trail for overnight stays?

Nearby shelters include Madison Spring Hut in the col between Mount Madison and Mount Adams and RMC cabins like Crag Camp, Gray Knob, and The Perch. Dolly Copp Campground, Moose Brook State Park, and lodging in Gorham and Pinkham Notch offer front-country options.

What are the primary points of interest along the trail?

Points of interest span waterfalls such as Stairs Fall, Coosauk Falls, and Hitchcock Falls; gorges like Devil’s Kitchen and the Bear Pit; ridgeline features including Blueberry Ledge, the four Howks, Madison’s summit, Osgood Ridge, and Gordon Ridge; and junctions like Randolph Path, Sylvan Way, Kelton Trail, Pine Link, and the Howker-Osgood junction.

How do the four “Howks” contribute to the trail’s challenge and scenic appeal?

Each Howk adds elevation gain and hands-and-feet scrambling to the climb. In return, they provide distinct outlooks: the Fourth Howk offers broad panoramas, the Third marks the shift to alpine terrain, while the Second and First showcase views toward Mount Madison and Randolph Valley.

What is the Devil’s Kitchen gorge, and how can hikers safely view it?

Devil’s Kitchen is a mossy, steep-walled chasm carved by Bumpus Brook. A short spur path leads to a viewpoint, but wet rocks are slippery; visitors should use caution and stay back from the edge.

How should hikers adjust plans for winter or early-spring conditions?

Winter brings deep snow, ice, and arctic winds. Hikers should be prepared to break trail with snowshoes and carry crampons and an ice axe. Consider descending via a safer route such as Valley Way and budget extra time. During spring melt or heavy rain, swollen brook crossings may be dangerous.

What essential gear and supplies are recommended for this trail?

Carry warm layers, rain gear, the ten essentials, and trekking poles. In winter add snowshoes, crampons, and an ice axe. Plan to carry all water needed; reliable sources include Bumpus Brook early on, a spring near the Pine Link junction, and seasonal water at Madison Spring Hut.

Can dogs accompany hikers, and what precautions should pet owners take?

Dogs are permitted but not recommended because of exposed ledges and rough terrain. If you bring a dog, ensure it is accustomed to scrambling, keep it leashed near cliffs, and pack extra water.